Jane Street Puzzle: Robot Baseball

Problem Statement

The Artificial Automaton Athletics Association (Quad-A) is at it again, to compete with postseason baseball they are developing a Robot Baseball competition. Games are composed of a series of independent at-bats in which the Batter is trying to maximize expected score and the Pitcher is trying to minimize expected score.

An at-bat is a series of pitches with a running count of balls and strikes, both starting at zero. For each pitch, the Pitcher decides whether to throw a ball or strike, and the Batter decides whether to wait or swing; these decisions are made secretly and simultaneously. The results of these choices are as follows.

- If the Pitcher throws a ball and the Batter waits, the count of balls is incremented by $1$.

- If the Pitcher throws a strike and the Batter waits, the count of strikes is incremented by $1$.

- If the Pitcher throws a ball and the Batter swings, the count of strikes is incremented by $1$.

- If the Pitcher throws a strike and the Batter swings, with probability $p$ the Batter hits a home run and with probability $1-p$ the count of strikes is incremented by $1$.

An at-bat ends when either:

- The count of balls reaches $4$, in which case the Batter receives $1$ point.

- The count of strikes reaches $3$, in which case the Batter receives $0$ points.

- The Batter hits a home run, in which case the Batter receives $4$ points.

By varying the size of the strike zone, Quad-A can adjust the value $p$, the probability a pitched strike that is swung at results in a home run. They have found that viewers are most excited by at-bats that reach a full count, that is, the at-bats that reach the state of three balls and two strikes. Let $q$ be the probability of at-bats reaching full count; $q$ is dependent on p. Assume the Batter and Pitcher are both using optimal mixed strategies and Quad-A has chosen the $p$ that maximizes $q$. Find this $q$, the maximal probability at-bats reach full count, to ten decimal places.

Solution

We can solve this problem by modeling it as finite-state Markov chain. Let the states be given by the set \(S = \left\{(b, s) : s \in \{0,\ldots,3\}, b \in \{0,\ldots,4\}\right\}\) where $(b, s)$ represents the state with $b$ balls and $s$ strikes. Depending on the decisions made by the pair of robots at a given state (swing or wait for the Batter and strike and ball for the Pitcher respectively), we transition to one of several possible states, each with their own transition probability.

If we knew the transition probabilities between all states as a function of $p$, then we can tune $p$ such that the probability of reaching a full count from the initial state $(0,0)$ is maximized. Thus we will approach the remainder of the problem in three steps:

- For a given state $(b, s)$ determine the optimal strategies for each player.

- Given the optimal strategies, determine the transition probabilities between states in the induced Markov chain.

- Determine the probability of reaching a full count and then select $p$ as to maximize it.

Optimal Strategies

Let $V(b, s)$ be the expected score of the Batter at state $(b, s)$. For a given state, we have a subgame where the Batter is trying to maximize the expected score and the Pitcher to minimize it. What are the optimal strategies for this subgame?

We can describe the strategies of the players using the concept of mixed-strategies. Let $x \in [0,1]$ and $y \in [0, 1]$ be the probabilities that the Batter plays swing and the Pitcher plays strike at state $(b,s)$ respectively. How can we determine what these two ought to be in an equilibrium strategy? Recall that in a Nash equilibrium, neither player can increase their objective by altering their current strategy. By the nature of our game, we can reason that neither player should use a pure strategy, as the opponent (or the player) could then deviate and improve their payout (Think rock, paper, scissors here – If your opponent always plays rock you should drop whatever strategy you are using and play paper). So what does a mixed strategy equilibrium look like in this case, does one even exist?

It turns out that, yes, one does exist! Since the subgame has a finite number of players (two) and a finite number of pure strategies (two each), it famously follows that the game will indeed have at least one Nash equillibrium in mixed-strategies. Now, can we find it?

Suppose that $(x, y)$ forms a mixed-strategy Nash equilibrium and that the Batter was considering changing $x$ in an attempt to increase their score. The expected payoff to the Batter using strategy $x$, for fixed $y$, is given by:

\[\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} V(b, s | x) & = x \underbrace{\bigg(y(4 p + (1 - p) V(b, s + 1) ) + (1 - y) V(b, s + 1)\bigg)}_{\text{Expected score from SWING}} \\ & \qquad + (1 - x)\underbrace{\bigg(y V(b, s + 1) + (1 - y) V(b + 1, s)\bigg)}_{\text{Expected score from WAIT}}. \end{aligned}\label{eq:payoff1} \end{equation}\]To determine their strategy $y$, the Pitcher should choose $y$ such that the Batter cannot do better by deviating from $x$. For fixed $y$, we can write (\ref{eq:payoff1}) as

\[\begin{equation} V(b, s | x) = x C_1(y) + (1 - x) C_2(y) \label{eq:payoff2} \end{equation}\]where $C_1(y), C_2(y)$ are constants that depend on $y$. Observe that (\ref{eq:payoff2}) is maximized at $x = 0$ when $C_1(y) < C_2(y)$, $x = 1$ when $C_1(y) > C_2(y)$, and any $x \in [0, 1]$ when $C_1 = C_2$. From this observation, it follows that if the Pitcher were to set $y$ such that $C_1(y) = C_2(y)$, then the Batter cannot improve their payoff by deviating from $x$.

We can solve for $y$ such that $C_1(y) = C_2(y)$. Doing so, we find that

\[\begin{equation} \boxed{y^*(b, s) = \frac{V(b + 1,s)-V(b,s + 1)}{V(b + 1,s) - V(b,s + 1) + p(4 - V(b,s+1))}}. \label{eq:y_strat} \end{equation}\]From (\ref{eq:y_strat}), since for any $(b, s) \in S$, we have that $V(b, s) \leq 4$ and $V(b + 1,s) \geq V(b,s + 1)$, it follows that $y(b, s) \in [0,1]$, which implies $y$ is a well-defined probability value.

Now, since the Batter and Pitcher share the same objective function, but different optimization directions, we can apply the same logic to ensure that the Pitcher cannot improve their payoff by deviating from $y(b, s)$, to find the corresponding Nash equilibrium strategy of

\[\begin{equation} \boxed{x^*(b, s) = y^*(b, s) }. \label{eq:x_strat} \end{equation}\]Now that we have found the unique Nash equilibrium strategy pair in this game 1 . We need to apply backwards induction using our state payoffs $V$ to find the exact value of each $x(b, s)$.

As mentioned in the problem statement, the payout to the Batter for striking out is $0$, for getting a walk is $1$, and for hitting a Homerun is $4$. Therefore the payouts are $V(b, 3) = 0$, $V(4, s) = 1$. We can solve for the Batter score function under the equilibrium strategies using the Mathematica code below.

B = 4;

S = 3;

(* Base Cases *)

V[b_ /; b == B, s_] := 1

V[b_, s_ /; s == S] := 0

(*Define equilibrium strategies*)

x[b_, s_] :=

x[b, s] =

Simplify[(V[b + 1, s] - V[b, s + 1])/(

4 p - (1 + p) V[b, s + 1] + V[b + 1, s])]

(*Define Payoff recurrence under optimal strategy*)

V[b_, s_] := V[b, s] = x[b, s]^2 (4 p + (1 - p) V[b, s + 1]) +

2 x[b, s] (1 - x[b, s]) V[b, s + 1] + (1 - x[b, s])^2 V[b + 1, s]

Note $V(b, s)$ and $x(b, s)$ only rely on states that are further along in the count (namely $V(b +1, s)$ and $V(b, s + 1)$) so we can use backwards induction to solve for them.

Transition Probabilities

Given that we now have a system to compute the optimal strategies and valuations of each state, to complete our Markov chain, we need to determine the transition probabilities between states.

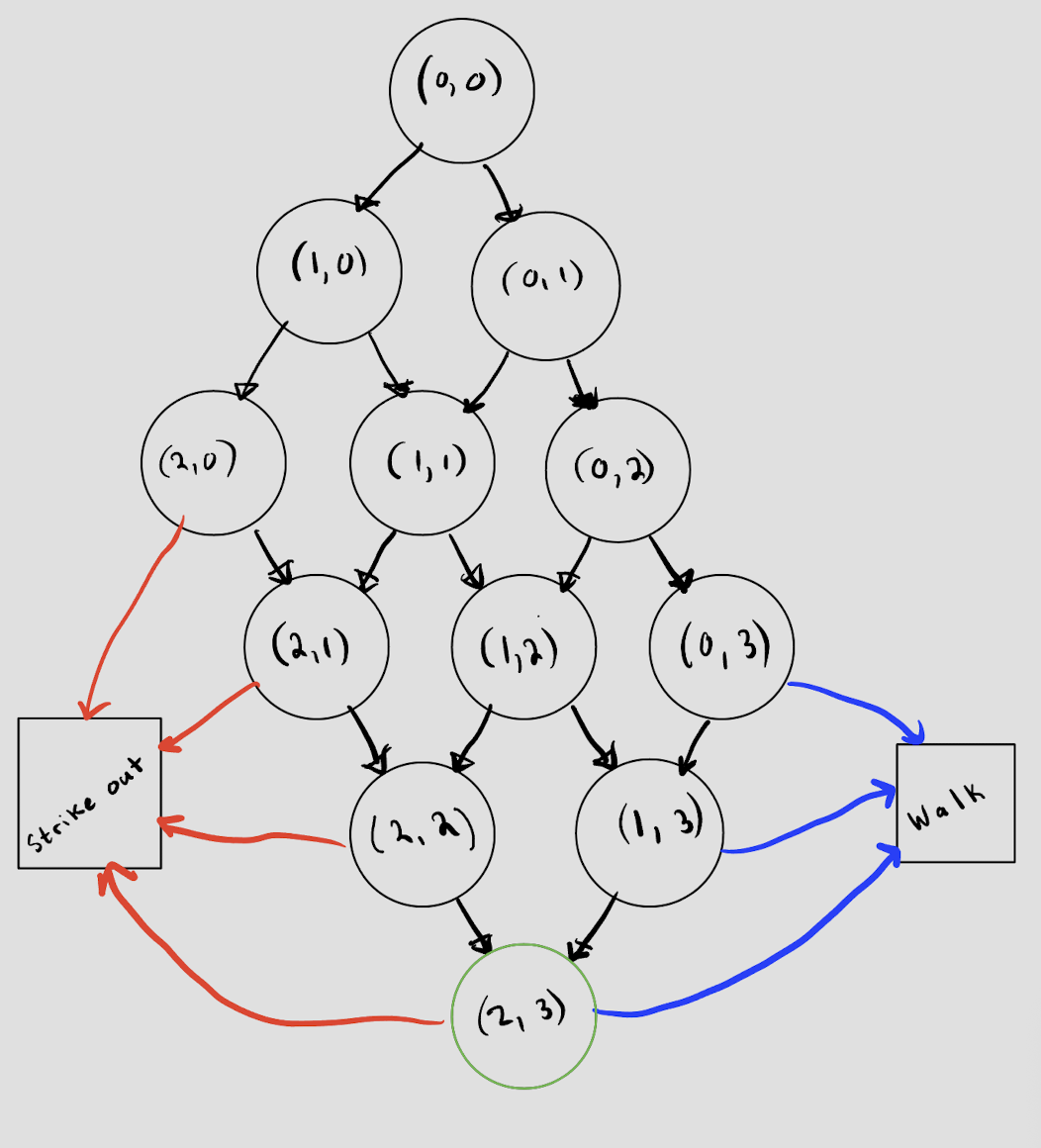

We will have the absorption states: $(b, 3)$ and $(4, s)$ for $b \in[3]$ and $s \in [2]$ which represent the outcomes of strikeout and walk respectively, and an auxiliary state that represents a Homerun, which can be reached from any non-terminal state in the game. We visualize the Markov chain below in Figure 1 (omitting the Homerun state for clarity).

Given that we are at the non-absorbing state $(b, s)$, we can either transition to $(b + 1, s)$, $(b, s + 1)$ or the Homerun state. Let $Q(b, s)$ be the probability of reaching a full count given we are at state $(b, s)$. We can write $Q(b,s)$ as

where $x$ is the Nash-equilibrium strategy given in (\ref{eq:y_strat}). The base cases for our function $Q$ are $Q(3, 2) = 1$ and $Q(b, s) = 0$ for any terminal state. For a given $p$, we can now use dynamic programming to compute $Q(0, 0)$, using the snippet of Mathematica code below. We want to know the value of $p \in [0,1]$ that maximizes the value of $Q(0, 0)$.

(* Base Cases *)

Q[b_ /; b == B - 1, s_ /; s == S - 1] := 1

Q[b_ /; b == B, s_] := 0

Q[b_, s_ /; s == S ] := 0

(*General recurrence *)

Q[b_, s_] := Q[b, s] = x[b, s]^2 (1 - p) Q[b, s + 1] +

2 x[b, s] (1 - x[b, s]) Q[b, s + 1] + (1 - x[b, s]) ^2 Q[b + 1, s]

Optimizing for a Full-Count.

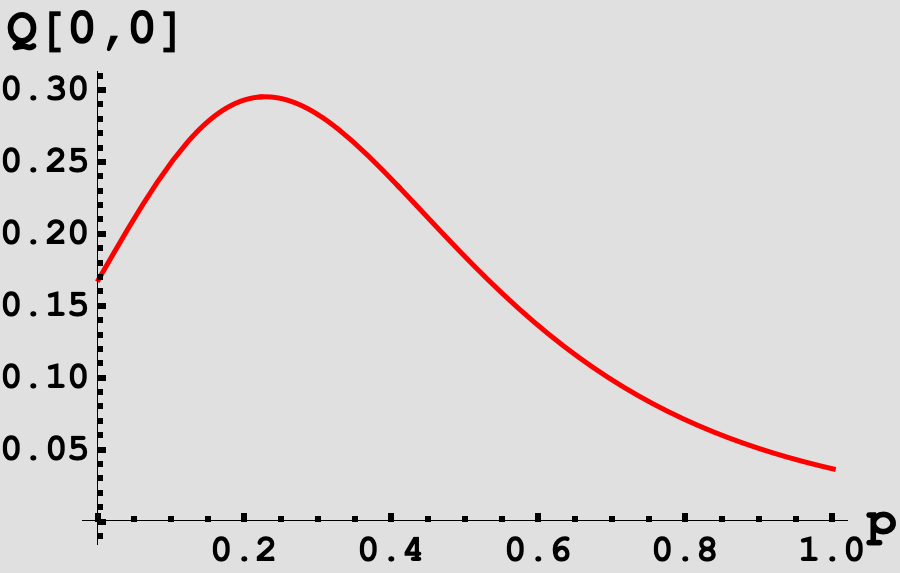

We can plot $Q(0,0)$ as a function of $p$.

Based on the figure, we can see the probability is unimodal in $p$ and we can use our favorite Binary Search method to determine the $p$ that maximizes our function. Alternatively, we can ask Mathematica to do this for us!

(* Maximize Q[0,0] over the interval [0,1] *)

NMaximize[{Q[0, 0], p >= 0, p <= 1}, p, WorkingPrecision -> 20]

Which produces a value of $\boxed{p^* \approx 0.2269732325}$ and the probability of reaching a full count in this case $\boxed{q \approx 0.2959679934}$, which is the answer to this month’s puzzle!

For fun, I experimented with changing the value of the Homerun state. In the given description, the value of a Homerun is 4 which implies the Batter has the bases loaded! What if this was instead a lower stakes scenario for the pitcher, and there were instead fewer points on the line if the Batter hit a Homerun. Below are the probabilities of reaching a full count, for various numbers of runners on base, as a function of $p$. We can see that with more players on base, the lower the value of $p$ needs to be to maximize the odds of reaching a full count!

-

Can you prove it? ↩

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: